There is a lot to say about Zack Snyder's (

300) just released

Watchmen, based on the 1985 graphic novel by Alan Moore (who also penned "V for Vendetta" and is widely credited for birthing the "dark" side of modern comics.) Not having read the original comic novel, however, I cannot say whether it is better, or worse, a travesty or a marvel of audaciousness. However, I do know that there is a tense relationship between the two, which seems to have affected how this movie has turned out. And so I will tell you that this is quite an original movie that at well over two and a half hours is, sadly, too long, too distanced, and a bit too tedious to really have the impact that I think this unique film deserved.

Firstly, if these Watchmen are also meant to be watch men - makers of clocks and watchers of human destiny and time - then the types of watches

dealt with here are more the melted clocks of Salvador Dali than the neatly backward-ticking timepieces in a movie such as

Benjamin Button. And I appreciate that. I like a movie that's willing to play with narrative and that travels in alternate realities. Snyder here has chosen to keep the movie set in Moore's original mid-eighties

milieux as its base

time frame of reference, which itself is a parallel 1980's to the real one (Richard Nixon is still President, somehow having repealed the Twenty-Second Amendment - and avoided Watergate - to be enjoying his fifth term). However, I think this decision to freeze the story in its original time may have been a mistake (I'll get to this more later) though I can appreciate how hard the pressure must have been not to tamper too much with what many fans must consider Moore's Bible. But I think that had the movie updated the base timeline to present day, many of its themes and obsessions would have held more resonance. But more on that in a bit.

It is perhaps unfair to criticize a movie based on Moore's graphic novel as being cliche - since it is Moore's story itself that lies as the inspiration for later films such as

The Dark Knight,

The Incredibles,

Hancock,

Sky Captain, and even perhaps some twists and turns of

X-Men. But the film does travel territory that we have been down now quite a few times before: the down-and-out superhero, the

quandary of superhuman power given to mortal hearts, the dynamics of a group of heroes whose vigilante actions are questionable, to say the least, and whose loyalties hang together through nothing more than their common obsessions and enemies.

Watchmen perhaps originated many of these tropes, and unfortunately, Snyder isn't able to update them

quite enough to be fresh again: though in

Watchmen, perhaps more than most other films of this type (with the exception, of course of

V for Vendetta), the society in which the superheros skulk is blacker than even our Dark Knights, and so their actions do take on the kind of heroic cynicism that have fascinated male teenagers for generations.

What is original about

Watchmen is that unlike

X-Men, where ability IS character, in this movie, it is the reverse: character - as it is slowly revealed in the film - IS the

super ability. And so we don't quite know what superpowers these watchmen are capable of until we learn who they are, how they came to be, and who they imagine themselves becoming. The characters in this story are revealed through a Raymond

Chanlder-

esque detective frame, so what we have here is a mystery in which, over two-and-a-half hours, the viewer learns what powers our heroes possess. All this is very rich and textual, and the abilities of the various characters - the Comedian, Dr. Manhattan,

Rorschach - slowly come into focus as we realize that each represents a kind of position on the moral continuum.

My favorite, and the audience's as well, I suspect, is

Rorschach, our narrator, a masked man with disturbingly moving blots rather than features, who is revealed to have a clear,

uncompromising moral judgement of the "scum" littering the city streets, and who prizes this moral certitude above all else: Robert

de Niro's taxi driver in

Taxi given mystical abilities. Inhabiting the opposite end of the moral spectrum is another Watchman, the intellectually superior Adrien

Veidt (a.k.a.

Ozymandias), whose ability to reach moral

compromise in his quest to establish a greater good is, shall we say, superbly dramatic. Inhabiting the middle ground between the two is Night Owl (or the second Night Owl, as this story spans two generations of Watchmen), the most human of the watchmen and the most humane; he needs the aid of his technological devices to see through the darkness more clearly - and he knows also that it is his judgement the others prize as representing the heart of the group.

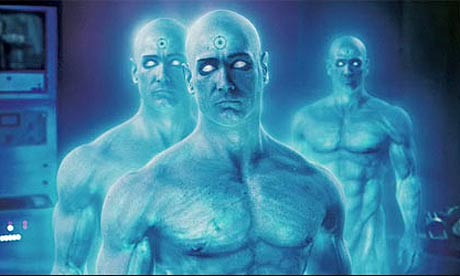

Circling these three are three other Watchmen: The Comedian, who's violently ironic comic detachment from life seems to be the initiator of many of the parallel stories herein; Dr. Manhattan, a glowing blue superhuman who, shall we merely say here, is detached from the living for entirely different reasons. And Laurie Jupiter (a.k.a. Silk Spectre II), who, I'm sad to say, seems to merely be the kick-ass babe the boys want to drool over. Why the women in this movie aren't given the same level of symbolic import as the men is, indeed, one of the ways in which this film squanders its potential.

Then there are the EARLIER generation of Watchmen to consider, some of which seem to have aged and some of which haven't, as well as a barely touched upon assortment of villains, girlfriends, colleagues, "real life" people, and other hangers on. All of which are entirely too much for a story that needs to get in and get out from an emotional core that is already distanced from us by that syrupy Raymond Chanlder-esque narration. Say what you want about Bryan Singer, but at least that guy knows how to craft a group of diverse, assorted characters around a single, centrally involving concept that they all must circle (think "who is Keyser Soze?"). The problem for Snyder is that he's lost himself to the Watchmen serial and the multiple parallel story lines without being able to pull from it a guiding central premise for the film.

That he seems to come up with one at the end is nice: the visual coda with Rorschach especially so. I just wish he had pulled that thread sooner, and trimmed out some of the unnecessary characters and fat.

And, back to my beginning comment, I also think updating the film to present day would have had even more impact. First, with the way time is shifted here, I am continually asking myself why we keep coming back to 1985. Why is that time the present? It was for Moore because when he wrote the Watchmen comics, it was the present, and this was a critique of Reganite culture - of the moment he was living in. Moore's story was written in the alternative present because it meant to be very contemporary: a comment on the cold war, an alternate version of the present, not the past. Perhaps Snyder felt that 1985 could stand in for 2005, Regan/Nixon standing in for Bush, Afghanistan (the first war) standing in for Iraq, without needing an update. But 2005 now too is already past (we're now dramatically in Obama's 2009 - a problem of historicity that a movie, which takes years to make, has to deal with more than a comic novel, which takes mere weeks to produce). And so, sadly, the central worry of the film (cold war standoff) feels out of date. And having an alternative past to our present moment feels like a betrayal of what Moore was up to, and the "real people" referenced in the film now feel entirely out of place. We are watching now not a critique of our culture but a critique of a history we no longer feel much worry or concern about.

And yet the film's dark vision and cynical view of realpolitik couldn't be more relevant. Shifting events in the story to Iraq, Pakistan, Bush I/II and terrorism rather than Vietnam and Afghanistan and cold war I believe would have spoken to the fears of OUR time and I think would have given the film the immediate emotional punch that it needed. For that was what Moore was going for originally, and by slavishly sticking to that historical element Snyder has drained all feeling from the movie, leaving us with something historical and clinical rather than immediate and meaningful.

There's also an issue of tone, which I don't think Snyder has gotten quite right. An example would be the real people: Nixon, Pat Buchanan, etc. They are caricatures of their real-life counterparts, yet they are neither extremely caricatured, nor are they at all similar. Rather, it was as if Snyder had pulled people off the street of the approximate gender and age of those people and told them to try and sound a little like them (perhaps never even having heard them). All this creates a kind of reality that is neither here nor there, when I think Snyder needed a reality that was most definitely somewhere: placed, perhaps, in an even more heightened alternative, and carrying us through to the world we recognize, or maybe barely recognize, today. George Stephanopolous, say, and an even more clown-mirror distorted version of him, rather than a stand-up comedian's version of McLaughlin Group.

Instead, it seems that Snyder was going for an interpretation, rather than a reinterpretation, of Moore: a loving introduction to the works of the maestro. And because this material really is subversive, what he's produced is a highly suggestive film that works backwards to introduce characters (intuitively rather than deductively), that wows us with transportation between time and place and suggestive images of war and murder that are both beautiful and disturbing (Snyder brings his 300 talents to this film, and it looks fantastic), that deals with the big themes of life and death, humanity and science, will and destiny, cynicism and belief. It is a movie that I have a hard time forgetting, and yet at times bored me to tears, and that I fear I may have made sound much more interesting than it is.

All of which is to say, it is a great film hampered by some very basic storytelling flaws: lack of focus, too much emotional distance, not enough risk-taking in digesting the source and giving us back something that captures the spirit more than the word of the original.

I really wish it had been better. A clear and moving deconstruction of our present political situation is highly called for, and the sci-fi / Chandler treatment of our particular moment on the brink of destruction, which is what's promised in the Watchmen vision, could have been fantastic. But as Don Rumsfeld used to say, sometimes you go to watch the movie you have, not the movie you might like to have.

Now if only Snyder had had the audacity to have quoted Rumsfeld, he really would have been on to something.